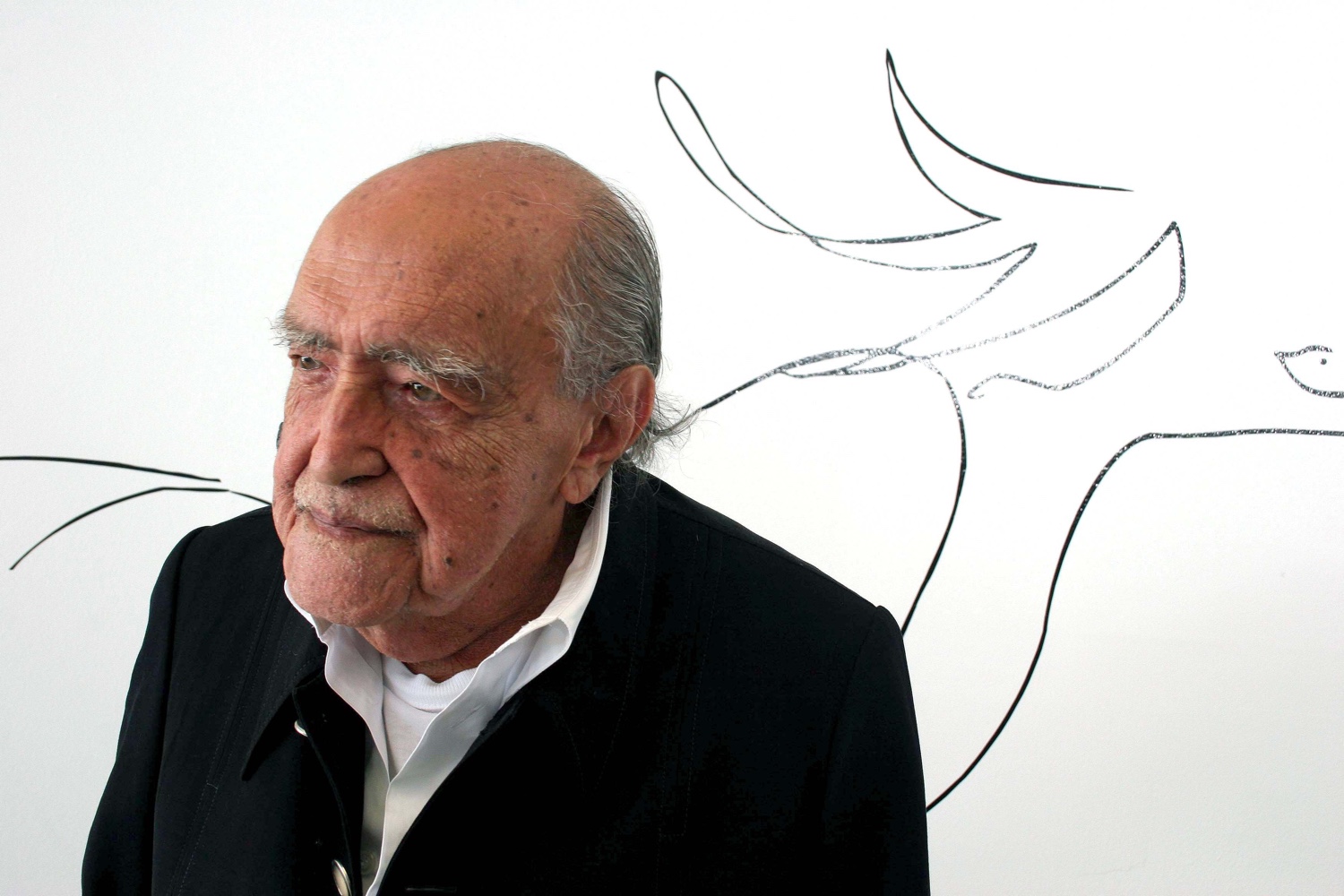

Dovetailing with a Rio focus – see Eight Rio Design Golds – this article spotlights Brazil’s best-loved architect, Senhor Oscar Niemeyer. Born in 1907 in Rio de Janeiro, Oscar Niemeyer, Brazil’s most famous architect, had not at first considered architecture as his vocation. Nevertheless, there was evidently something in his psyche, and Niemeyer did enjoy drawing from a young age (his mother recalled that as a baby, Oscar appeared to draw in the air with his fingers).

‘Oscar’ (as he is affectionately known in Rio) hailed from a wealthy, bourgeois family, and in his early days felt little compulsion to work, choosing instead to enjoy a more bohemian lifestyle. As a young man, Niemeyer reportedly loved four particular things: drawing, nature, women and communism. Indeed, Niemeyer’s proclivity for curves (the female form) and natural lines are evident throughout his many works. His style of modernism was distinctly Brazilian, both whimsical and romantic.

Seminal Works

With his penchant for drawing, Niemeyer graduated in 1934 with a degree in architecture from Rio’s Escola Nacional de Belas Artes (School of Fine Arts). Before graduating, he was hired by architect Lucio Costa to work on the modernist Ministry of Education and Health Building in Rio, known also as the Palácio Gustavo Capanema. While working on this project, Niemeyer met Le Corbusier who was tasked with evaluating the design.

In 1940, Niemeyer designed the Church of St. Francis de Assisi in the Pampulha region of Belo Horizonte, a city in eastern Brazil. The design was a marked rejection of the harsh lines and rational architecture seen in many modernist buildings, accentuating instead a more feminine shape by using natural and harmonious curves. Niemeyer’s fascination with the female form was fodder for his many designs.

In 1947, Niemeyer worked with Le Corbusier to design the United Nations Headquarters in New York City. The two architects developed their own distinctive designs: Le Corbusier conceived a basis for the headquarters and Niemeyer drew up the final plan. The building was completed in 1952 and Niemeyer’s collaboration with Le Corbusier earned him much respect in Brazil.

Brasilia

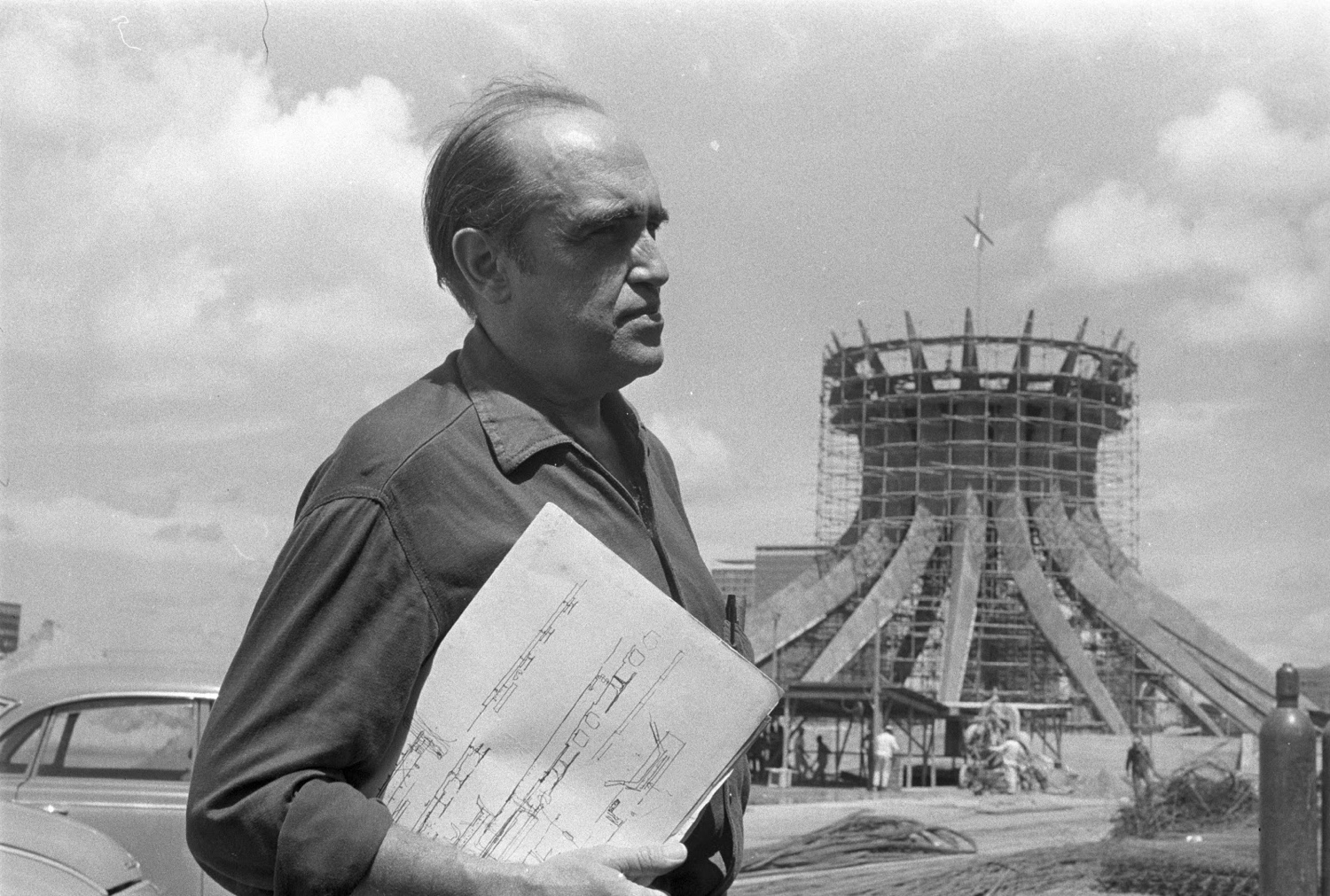

It was Niemeyer’s work on Brasilia, Brazil’s new capital, that perhaps cemented his reputation as an architect. Created from nothing between 1956 and 1960, and located in the country’s central west, Brasilia was key to President Juscelino Kubitschek’s national modernisation project. Niemeyer again worked with Lucio Costa to build the city, generating a monumental landmark in the history of town planning and a study in modernist urbanism. Brasilia was built around the principles of harmony and symmetry, a utopia created and curated with much flair, imagination and innovation. It truly was a work of genius and a place that demonstrated the tenets of Le Corbusier’s 1946 doctrine How to Conceive Urbanism. Brasilia was inaugurated as Brazil’s capital city in 1960 (unseating Rio) and was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987, the only urban centre to be built in the 20th century that has been awarded this status.

Key Brasilia buildings designed by Oscar Niemeyer

Communism

Niemeyer was committed to Communist ideology – a fact reflected throughout his work – and he joined the Brazilian Communist Party in 1945 (later acting as the party’s President between 1992 and 1996). Following his work on the United Nations Headquarters, Niemeyer was appointed as dean of Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. However, his membership of the Brazilian Communist Party resulted in the US government refusing him an American work visa. The 1964 Brazilian military coup (supported by the USA) left Niemeyer in a precarious position. Known as someone with left-wing beliefs and tendencies, his office was ransacked, and Niemeyer left the country, seeking refuge in France. In Paris, Niemeyer designed a modernist and bold headquarters for the French Communist Party, a structure set in stark contrast to the city’s many grandiose and stately architectural gems. Brazil’s military dictatorship lasted until 1985, after which time Niemeyer returned to live in his home country.

Niemeyer considered himself to be a pessimist and a realist. His commitment to the Communist Party was one based on change and fighting injustice, working together to achieve a better world for all.

Longevity

In 1996, aged 89, Niemeyer completed what many believe to be his greatest work: the Niterói Contemporary Art Museum in the city of Niterói, sitting on Guanabara Bay, opposite Rio. Niemeyer had a long and prolific life – he died in 2012 aged 104 and produced more than 500 buildings – and his architectural legacy endures, prospers and excites. Just as the architect himself, his numerous achievements are enjoying longevity, their forms never outdated. As with any great architect, Niemeyer received many awards and accolades, including the Pritzker Prize for Architecture in 1988. Yet more inspiring was his commitment to and belief in the fundamental power of architecture. Niemeyer was still working up until his death, championing his belief in a better world and fighting for the amelioration of all over the privileged few.

Of the architect, Oscar Niemeyer concluded: “The architect is a citizen just like any other, always open to serve any kind of program (sic) presented to him, be constantly aware of society’s need to change, to foster a fair and solidary world” (Source: ArchDaily).

Bibliography:

Brasilia. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/445/

Oscar Niemeyer Biography. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.biography.com/people/oscar-niemeyer-9423385

Oscar Niemeyer: Biography, Buildings & Works. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://study.com/academy/lesson/oscar-niemeyer-biography-buildings-works.html

Fournier, G. (2006). Urban planning, Brazil, communism … What makes Oscar Niemeyer run? l’Humanité. Translated from French by P. Bolland. Retrieved from http://www.humaniteinenglish.com/spip.php?article69